Perhaps what made her a good teacher was the great actress in her past, that oftremarked link to Ellen Terry. A bit of a reach for a relation, but that had never stopped Francesca. The Ellen Terry connection was one of the myths of the Manor.

Amelia took the myth at face value for her student years. But later, when she returned to teach at the Manor, she investigated. The facts were that “the Master,” G. F. Watts, painter of mythological scenes, fell in love with Ellen Terry when she was a mere fifteen, and playing on the London stage. He, forty-seven, considered adopting her but was told she was too old; he asked his friends if he might marry her, but they said she was too young. He kissed her, and she thought she was with child and told her mother they must be married. She wanted, she said, to live with his pictures.

It is unclear if the marriage was ever consummated; Ellen was found cast down the staircase on her wedding night, weeping and clinging to the banister. Watts liked to fumble around, someone said later, but he couldn’t do much. When they divorced he paid her an allowance to keep her with her parents, and away from the immoral life of the theatre. She went on to have a glorious career and several more husbands.

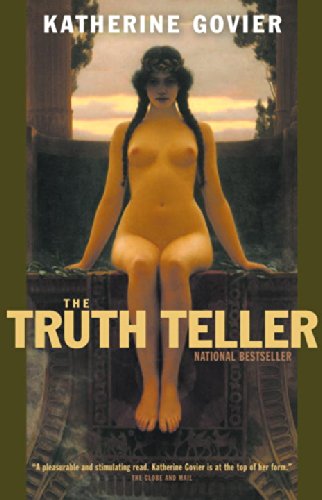

After Ellen, Watts conceived a passion for her playmate, Lily. Having learned his lesson, he adopted her and married a woman more his age. Amelia classified it as one of those Victorian stories where unusual sexual proclivities went under the rubric of charity. Plainly put, the Master liked little girls. You could feel it in his painting of Lily. The fey presence of the young girl with her basket of flowers was infused with erotic longing. One could see her arrogance, her sense that she held the old painter in thrall; one felt too that the Master had pinioned her, a lovely butterfly on a corkboard.

A fair exchange.” – Katherine Govier, The truth teller